Mr. Ducard said that original videos aimed at a younger audience had “always been one of the anchors of YouTube.” (Stampylonghead, in less than a decade, went from being a video game-obsessed teenager in southern England to having one of the 10 most popular YouTube channels in the world.) But children who have grown up with the site are developing a relationship with it that is different from that of their older siblings and parents.

Ganymede: Facts About Jupiter's Largest Moon

Jupiter's moon Ganymede is the largest satellite in the solar system. Larger than Mercury and Pluto, and only slightly smaller than Mars, it would easily be classified as a planet if were orbiting the sun rather than Jupiter.

The moon likely has a salty ocean underneath its icy surface, making it a potential location for life. The European Space Agency plans a mission to Jupiter's icy moons that in 2030, is planned to arrive and put special emphasis on observing Ganymede.

Facts about Ganymede

Age: Ganymede is about 4.5 billion years old, about the same age as Jupiter.

Distance from Jupiter: Ganymede is the seventh moon and third Galilean satellite outward from Jupiter, orbiting at about 665,000 miles (1.070 million kilometers). It takes Ganymede about seven Earth-days to orbit Jupiter.

Size: Ganymede's mean radius is 1,635 miles (2,631.2 km). Although Ganymede is larger than Mercury it only has half its mass, classifying it as low density.

Temperature: Daytime temperatures on the surface average minus 171 degrees Fahrenheit to minus 297 F, and night temperatures drop to -193C. In 1996, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope found evidence of a thin oxygen atmosphere. However, it is too thin to support life as we know it; it is unlikely that any living organisms inhabit Ganymede.

Magnetosphere: Ganymede is the only satellite in the solar system to have a magnetosphere. Typically found in planets, including Earth and Jupiter, a magnetosphere is a comet-shaped region in which charged particles are trapped or deflected. Ganymede's magnetosphere is entirely embedded within the magnetosphere of Jupiter.

Characteristics of Ganymede

Ganymede has a core of metallic iron, which is followed by a layer of rock that is topped off by a crust of mostly ice that is very thick. There are also a number of bumps on Ganymede's surface, which may be rock formations.

In February 2014, NASA and the United States Geological Survey unveiled the first detailed map of Ganymede in images and a video animation created using observations from NASA's Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft, as well as the dedicated Jupiter-orbiting Galileo spacecraft.

Ganymede's surface is made up of primarily two types of terrain: about 40 percent is dark with numerous craters, and 60 percent is lighter in color with grooves that form intricate patterns to give the satellite its distinctive appearance. The grooves, which were likely formed as a result of tectonic activity or water being released from beneath the surface, are as high as 2,000 feet and stretch for thousands of miles.

It is believed that Ganymede has a saltwater ocean below its surface. In 2015, a study by the Hubble Space Telescope looked at Ganymede's auroras and how they change between Ganymede's and Jupiter's magnetic fields. The “rocking” seen by the auroras gives evidence that the probable ocean underneath is salty, more salty than oceans of Earth, scientists said at the time.

Some scientists are skeptical that Ganymede could host life, however. Due to its internal structure, it is believed that the pressure at the base of the ocean is so high that any water down there would turn to ice. This would make it difficult for any hot-water vents to bring nutrients into the ocean, which is one scenario under which scientists believe extraterrestrial life would occur.

VOCABULAR

- embedded - встроенный

- unveiled - открыт

- auroras - сияние

YouTube’s Young Viewers Are Becoming Its Creators

Like a lot of American adolescents, 14-year-old Archer Murray and his 11-year-old sister, Cady, spend their free time reading, playing games, talking with friends and watching videos on the Internet. With their laptops, cellphones and tablets, they click on YouTube, searching for a range of content like episodes of Japanese cartoons and tips on what to do in Minecraft.

They almost never turn on a television set or watch anything produced by a broadcast or cable network. Their father consumes a typical adult TV diet of sitcoms, prestige dramas and reality shows, but the Murray children are embracing the new kind of broadcasting, which circumvents the old media gatekeepers and delivers content better tailored to their interests.

The traditional television industry keeps trying to find ways to draw those young eyes, by littering their programs with social media hashtags and giving development deals to Twitter and YouTube users who have hundreds of thousands of followers. But viewers under 18 are not seeing the Internet as a farm system for Hollywood, the way the major studios hope.

Malik Ducard, the global head of family and learning at YouTube, sees this dynamic every day — both at work and at home, where his children are 13, 10 and 7. “My personal belief is that kids travel from medium to medium and vehicle to vehicle seamlessly,” he said. “It’s become something innate and natural to this generation.”

Part of Mr. Ducard’s job is to nurture that relationship. His company recently initiated YouTube Kids, a redesigned version of its standard mobile app, with easier-to-use controls and more fine-tuned parental restrictions to help keep children away from some dark and abusive corners of YouTube. In the first month that the app was available, it was downloaded two and a half million times, according to YouTube.Continue reading the main stor

YouTube also works to promote some family-friendly creators, like Joseph Garrett, or “Stampylonghead,” who started posting Minecraft-themed videos when he was a teenager. Now in his mid-20s, Mr. Garrett has a deal with Maker Studios, a producer of short-form videos and a subsidiary of the Walt Disney Company, to produce educational content for schools with the new series “Wonder Quest.”

YouTube users must be 13 or older to have an account, which allows them to upload videos and comment on videos. Because of the age restriction, and because the site hosts 400 hours of new content every minute and generates billions of page views, detailed demographic data for younger users is hard to come by. But year to year, the number of hours people spend watching videos on YouTube keeps growing — up 50 percent over last year, according to the site’s own statistics page — and a lot of those watchers make the transition to becoming creators. Children who have grown up with short, quirky videos online have started to see them as another form of communication, akin to the conversations they have in the comments section of websites.

Much of the news coverage of YouTube, Vine and Instagram has focused on “viral videos,” and on an emerging breed of celebrities who either make short comedy sketches or rant into the camera about their lives. Those kinds of clips and personalities are undeniably popular, but they alone are not what is drawing the under-18 crowd.

The credit for that belongs just as much to the likes of Mr. Garrett and Emile Rosales, who goes by “Chuggaaconroy.” They are less interested in personal branding than in sharing their enthusiasm. Like Stampylonghead, the 25-year-old Chuggaaconroy has been online since he was a child, when he first started using his pseudonym as a player and forum ID. (A lot of the handles used by YouTubers are carry-overs from the nonsense names they came up with when they were younger.)

Mr. Rosales also works within the “Let’s Play” genre, making videos that consist of him and his friends playing Nintendo and cracking jokes. And “work” is the right word. With nearly a million subscribers to his YouTube channel and more than 760,000,000 views of his video game walk-throughs, Chuggaaconroy earns enough money from goofing on games that making videos has become his only job.

Mr. Rosales said he did not have much day-to-day interaction with anyone at YouTube. (“Every now and then, they’ll email me to ask me to try out some new feature on the site,” he said. “And I think they invited me to a company party one time.”) And because his videos occasionally include some rough language, they would not be allowed on the YouTube Kids app.

Nevertheless, his fan base includes a healthy number of preteens — including the Murray children — who found his clips by following the trail of “if you liked that, try this” suggestions offered by YouTube. Younger fans often leave thoughtful comments or post their own artwork and response videos, Mr. Rosales said. What they create is “really amazing to see,” he added.

VOCABULARY

- adolecent - подросток

- prestige - престиж

- gatekeeper - сторож

- restriction - ограничение

- anchor - якорь

Slavoj Žižek – The Elvis of Philosophy?

“The thinker of choice for Europe’s young intellectual

vanguard”, a “punk philosopher”, “a rollercoaster

ride”, “sometimes bonkers but never

boring” and “the Elvis of philosophers” are among the many

things that have been said about Slovenian philosopher, culture

critic and psychoanalyst Slavoj Žižek and his works. Žižek

(born 1949), who packs out public lecture halls around the

world, is currently International Director of the Birkbeck

Institute for the Humanities in London and Senior Researcher

at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Ljubljana –

from which he was expelled in the 1970s because his PhD

thesis was “too Hegelian and not Marxist enough.” He’s made

films too, including one entitled The Pervert’s Guide to the

Cinema (2006). There is even an Institute of Žižek Studies.

When Slovenia became independent from Yugoslavia in 1991,

it instituted a four-person Presidency, for which Žižek stood.

He came fifth.

Žižek has a Stakhanovite work ethic and has published some

sixty books, six in 2014 alone. His main influences are Hegel,

Marx, Jesus, and the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. You

meet the same ideas, even identical chunks of text, in several of

Žižek’s works; so if you don’t grasp an idea first time, you’ll

have a better chance the second or third time around. He illustrates

his points with a wide range of cultural references, from

classic Hitchcock films such as Psycho and Rear Window, more

recent films such as Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Slayer (a lesserknown

facet of the US President’s early career), to Wagner,

Mozart, contemporary Hegelian philosophers such as Catherine

Malabou, and Jane Austen, who he claims was a Hegelian

writer, though I doubt she was aware of it. But then, after Derrida,

we know that what the author intends is not the point.

Žižek uses many jokes in his works, which he claims illustrate

profound philosophical points. They are often racist, sexist, antisemitic,

or combinations of all of these. He can be provocative,

rude and aggressive – hence the punk comparison – although

the punk-rockers of the 1970s were not generally accomplished

musicians, whereas Žižek is an extremely erudite thinker. He

likes to study and quote writers who are normally considered

right-wing because he doesn’t think the left has come up with

many original ideas in recent times. And the left does seem to be

on the defensive in most of the West. In Europe, it’s on the run

from right-wing anti-immigration populist movements.

Žižek’s very fond of arresting statements such as “Hegel was

the first post Marxist”, “Gandhi was more violent than Hitler”

and “ only a radical leftist can be a true conservative today.”

When talking about the Frankfurt School philosopher

Theodor Adorno, Žižek wrote that: “the brilliant paradox

works precisely in the same manner as the Wagnerian leitmotif: instead of serving as a nodal point in the complex network of

structural mediation, it generates idiotic pleasure by focusing

attention on itself.” But

he could have been talking about himself, because Žižek’s own

work is full of brilliant paradoxes which force attention on

themselves. The question is, is he just forcing attention on himself,

or does he have a coherent philosophy?

Hegel As The First Post-Marxist

One of Žižek’s key claims is that we are living in the End Times. Capitalism is dying. But we don’t know what to replace it with. Communism as developed by Marxists has been a disaster: firing squads, gulags, mass starvation, and miserable mediocrity even when it was working well. So to find out where we went wrong we have to go back past Marx, to Hegel.

Žižek’s first book in English, The Sublime Object of Ideology, was published in 1989 and puts forward the idea that Hegel (1770- 1831) was the first post-Marxist. Hegel died when Marx was thirteen – seventeen years before Marx and Engels published the Communist Manifesto. So how can this idea be credible?

What Žižek means is that for Marxists all conflicts and struggles – national, race, gender, sexuality, ecological – in society can and must be subsumed under the class struggle, and they’ll be resolved when the proletariat takes power, and not before. But it’s not so for post-Marxists, and it was not so for Hegel, either.

By the 1950s it was becoming evident that the proletariat, as generally understood then in the West – white male skilled and semi-skilled manual workers, and labourers – were not going to lead a revolution. They had been bought off by the cars and TVs provided by consumer capitalism. So revolutionaries had to look to marginal and excluded minorities, such as blacks, gays, students, and the ‘lumpenproletariat’. This thesis was formulated and popularised by Herbert Marcuse in One Dimensional Man (1964). Hegel had said something similar. First, that there was not one overriding conflict that would subsume all the others; and second, that there would always be a pobel – a rabble on the fringes of society who would never be fully integrated into it. Žižek returns to this theme in Less than Nothing, his major work of 2012, in which he nobly tries to bring Hegel back to the centre of the philosophical stage by saying that the pobel, like the poor, will always be with us. The underclass may erupt from time to time in outbursts of violence, as in parts of London in 2011, or LA in 1992, or Paris in 2005, but the violence was largely directed against local shopkeepers and business owners, the people closest to them, and is ultimately futile. The underclass don’t have the skills, or the will, to transform society.

Is Capitalism Nearing Its End?

According to Žižek in Living in the End Times, the ‘four horsemen of the apocalypse’ are:

- Worldwide ecological crisis (global warming, resource

depletion).

- Imbalances within the economic system (the financial crisis

of of 2008).

- The biogenetic revolution.

- Exploding social divisions (the riots, the growth of various

type of fundamentalism, at the moment, notably Daesh/Isis).

Hence his view that capitalism is nearing its end.

I’m somewhat sceptical of this claim. Trotskyists have been telling us that capitalism is nearing its final crisis – its ‘death agony’ – since the 1930s, but even though it lurches from crisis to crisis with greater or lesser frequency, it’s still with us. However, capitalism’s solution to social tensions and problems has always been continuing economic growth, and it’s hard to see how the planet can support that indefinitely.

In Trouble in Paradise, one of his shorter and more accessible

works, published in 2014, Žižek takes issue with the people we

might call right wing optimists – those who think that the present

is the best time in human history, thanks to capitalism. He

also quotes the sociobiologist Stephen Pinker, who in The

Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), argues that human society is

less violent now than it’s ever been. This view seems somewhat

difficult to square with our experience of Isis/Daesh, the desperate

plight of the Syrian refugees, and the continuing violence

in Palestine. No doubt the optimists would claim that

these are mere eddies in the calm river of history, exceptions

rather than the rule. Perhaps it’s only the West that’s in the

economic doldrums: the developing world is continuing to

grow, to such an extent that there are now economic migrants

going from Portugal back to its former colony, Angola.

In Trouble in Paradise, one of his shorter and more accessible

works, published in 2014, Žižek takes issue with the people we

might call right wing optimists – those who think that the present

is the best time in human history, thanks to capitalism. He

also quotes the sociobiologist Stephen Pinker, who in The

Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), argues that human society is

less violent now than it’s ever been. This view seems somewhat

difficult to square with our experience of Isis/Daesh, the desperate

plight of the Syrian refugees, and the continuing violence

in Palestine. No doubt the optimists would claim that

these are mere eddies in the calm river of history, exceptions

rather than the rule. Perhaps it’s only the West that’s in the

economic doldrums: the developing world is continuing to

grow, to such an extent that there are now economic migrants

going from Portugal back to its former colony, Angola.

The country that Žižek says typifies the ‘paradise’ in which

we’re now living is South Korea. Here “we find top economic

performance, but with frantic intensity of the work rhythm;

unbridled consumerist heaven, but permeated with the hell of

solitude and despair; abundant material wealth, but with the

desertification of the landscape; imitation of ancient traditions,

but with the highest suicide rate in the world”. He

goes on to say (in yet another ‘brilliant paradox’): “today’s conservatives

are not really conservative. While fully endorsing

capitalism’s continual self-revolutionising, they just want to

make it more efficient by supplementing it with some traditional

institutions (religion, for instance) to constrain its

destructive consequences for social life and to maintain social

cohesion. Today, a true conservative is the one who fully

admits the antagonisms and deadlocks of global capitalism,

who rejects simple progressivism, and who is attentive to the

dark obverse of progress. In this sense, only a radical Leftist

can today be a true conservative”.

Communism

Žižek talks about communism in most of his works, but he uses the word in several different ways. At the end of Trouble in Paradise he says that “Communism today is not the name of a solution but the name of a problem, the problem of commons in all its dimensions – the commons of nature as the substance of our life, the problems of our biogenetic commons, the problem of our cultural commons (‘intellectual property’), and last but not least, the commons as the universal space of humanity, from which no one should be excluded”.

Is this just another example of his idiosyncratic use of words? Elsewhere Žižek characterises communism as the collective provision of bridges, streetlights, flood barriers – all things that we take for granted now, but which haven’t always been uncontroversial.

Communism for Žižek is encapsulated in the music of Eric

Satie, who, Žižek tells us, was on the Central Committee of

the French Communist Party in the 1920s. Satie said his music

was intended as a backdrop, and that it didn’t matter what

order the sections of his pieces were played in. Žižek claims

that this is communism in music: “a music which shifts the listener’s

attention from the great theme [as explored by, say,

Beethoven] to its inaudible background, in the same way that

communist theory and politics refocus our attention away

from heroic individuals to the immense work and suffering of

ordinary people”.

Communism for Žižek is encapsulated in the music of Eric

Satie, who, Žižek tells us, was on the Central Committee of

the French Communist Party in the 1920s. Satie said his music

was intended as a backdrop, and that it didn’t matter what

order the sections of his pieces were played in. Žižek claims

that this is communism in music: “a music which shifts the listener’s

attention from the great theme [as explored by, say,

Beethoven] to its inaudible background, in the same way that

communist theory and politics refocus our attention away

from heroic individuals to the immense work and suffering of

ordinary people”.

Another key point about Žižek is that he thinks that the three most important philosophers are Plato, Descartes and Hegel. Plato’s forms don’t exist in the real world but they are what we measure the real world against. Similarly, communism is the ideal society which we can never attain, but also the yardstick against which we measure our social and political arrangements. His description of communism, as given above, is somewhat vague and hazy, and he says it’s necessarily so. Yet how can we judge our societies if we only have a vague idea of the standard we’re judging them against? Other utopians, such as Thomas More, William Morris, and Plato himself in the Republic, went into quite a lot of detail about their ideal societies.

What Is To Be Done?

If communism is the question rather than the answer, what should we do, here and now, to face down the four horsemen and move towards the vague ideal? In another arresting paradox, Žižek says: “Don’t act: think.” But he does sketch a few prescriptions for action.

One of the ideas he does consider to be worth pursuing is

that of a ‘Citizen’s Income’, to which everyone is entitled

whether they work or not. It has been introduced, or is being

introduced, in one form or another, in Utrecht, Finland, Brazil

and Alaska. Put forward by Thomas Paine in the Eighteenth

Century, it has been advocated by thinkers on both the left and

right. It appeals to the left because everyone has a guaranteed

level of income, and so security, whatever their circumstances,

and it’s also a way of resolving the age-old contradiction

between freedom and equality. It’s also been advocated by rightwing

philosophers such as the German Peter Sloterdijk, since it

guarantees that people will be able to afford to buy the goods

capitalism produces. Sloterdijk argues that it’s not the rich who

exploit the poor any more, it’s the other way round. We’re all

dependent on creative geniuses such as Steve Jobs and George

Soros, who give to the world out of a sense of honour and pride.

We are all social democrats now, in that it’s the redistribution of the wealth created by the gifted few that keeps the system going. A nice, plausible thesis, until you consider who it was that the state had to bail out in the recent economic crisis.

What are the problems with the idea of the Citizen’s Income? It will lead to an improvement in the pay and conditions of workers at the bottom of the pile; but will they become so choosy that the worst jobs won’t get done? And if so, will it matter? There is already a great deal of resentment about welfare claimants. How could we sell people the idea that work becomes purely voluntary, a matter of ‘honour’ and ‘pride’? And perhaps the biggest issue is, who counts as a citizen – who is included and who’s excluded? The spectre of right-wing populism raises its head again here. Perhaps the Citizen’s Income idea needs to be implemented initially on a European scale before trying to apply it to the world as a whole. In any event, we should watch the current experiments with interest.

In fact, Žižek is very keen on Europe, and considers social democracy its finest achievement. But Europe needs to be remade in very different terms – he thinks the contemporary EU requirement that all EU states should eradicate their debt to be absurd, a recipe for economic depression. He held out great hopes for the Syriza government in Greece, but not so much now since it seems to have capitulated to Germany’s demands.

In Trouble in Paradise he says that we need a “new Master”

(sic), a Thatcher of the Left: a leader who would repeat Margeret

Thatcher’s transformation of the field of presuppositions

shared by the political elite of all persuasions, but in the opposite

direction. But “a true Master is not an instrument of discipline

or prohibition.” His message is not ‘you cannot’ or ‘you

have to’ but a liberating ‘you can’. Steve Jobs came close to the

concept of a true Master when he said “It’s not our job to figure

out what people want. It’s our job to figure out what we want.

It’s then up to the people to decide if they will follow”

VOCABULARY

- bonkers - помешанный

- mediocrity - посредственность

- evident - очевидный

- doldrums - дурные настроения

- uncontroversial - бесспорный

- horsemen - всадники

Dueling Desserts

To Marc Murphy, executive chef and restaurateur of Landmarc and Ditch Plains, Italian desserts are perfect. They’re simple, not too sweet, and served in smaller, just-right portions. “It’s not about [being] over the top, six layers of whipped cream, and sparklers coming off the top like you do in France, with tempered chocolate and complexities like that,” Murphy says. “It’s taken a bit differently over in Italy. You just have to have something right before the espresso and the grappa.” In his time spent living in Italy (he was born in Milan), Murphy says it was common for diners to be served whatever fruit was fresh at the market that day for the dessert course—a simplicity he says is underrated in many U.S. restaurants, where decadence rules the dessert menu.

“If I had to describe Italian desserts in one word, it would be subtleness,” he says. “The subtlety of flavor is, I think, the reason that Italian desserts can be underappreciated and could use some more recognition.” Murphy is certainly doing his part to get simple Italian desserts the recognition they deserve by allowing subtlety to shine through in the dessert menu at his latest restaurant, Kingside. We had Murphy go to bat for his beloved tiramisu, while chef Adrienne Bandlow stands up for the other Italian staple: cannoli. In this corner: Tiramisu The Italian word tiramisù translates literally to “pick me up.” And after years of stagnation in the U.S. market, the dessert has been in need of a little elevation. The Pistachio Tiramisu at Kingside in uptown New York City does just that by presenting a fresh, flavorful, and elegant spin on the old mainstay. “Tiramisu is one of those desserts that was around a lot in America, and maybe even overused at a certain point,” Murphy says. “It was great for so many years for a reason, and when I found this new twist, I just felt like, ‘Tiramisu is not dead! It’s still delicious and exciting.’”

Tiramisu is traditionally made by layering coffee-dipped

ladyfingers with a cocoa-flavored mixture of eggs, sugar,

brandy, and Mascarpone cheese. But while visiting some

friends in Rome, Murphy discovered a new take to tiramisu

that he loved: Adding pistachios, another favorite flavor in

Italian cuisine, but one that he had never seen used in this

way. He was especially surprised to see this twist in Rome,

where the cuisine is notoriously entrenched in tradition and consumers are wary of innovation.

“It’s a place where, if it doesn’t taste like mom made it, then

it’s not right. So this really surprised and impressed me,” Murphy

says.

He immediately put the recipe on the dessert menu when

he opened Kingside in 2013. The Pistachio Tiramisu also

got a spot in his April 2015 cookbook, Season with Authority.

While the recipe contains all of the classic ingredients, the

pistachio paste, whole shelled pistachios, and a pinch of cream

tartar bring a little something different to the table, especially

when coupled with its presentation in a small glass jar.

Tiramisu is traditionally made by layering coffee-dipped

ladyfingers with a cocoa-flavored mixture of eggs, sugar,

brandy, and Mascarpone cheese. But while visiting some

friends in Rome, Murphy discovered a new take to tiramisu

that he loved: Adding pistachios, another favorite flavor in

Italian cuisine, but one that he had never seen used in this

way. He was especially surprised to see this twist in Rome,

where the cuisine is notoriously entrenched in tradition and consumers are wary of innovation.

“It’s a place where, if it doesn’t taste like mom made it, then

it’s not right. So this really surprised and impressed me,” Murphy

says.

He immediately put the recipe on the dessert menu when

he opened Kingside in 2013. The Pistachio Tiramisu also

got a spot in his April 2015 cookbook, Season with Authority.

While the recipe contains all of the classic ingredients, the

pistachio paste, whole shelled pistachios, and a pinch of cream

tartar bring a little something different to the table, especially

when coupled with its presentation in a small glass jar.

By drawing attention to a dish that was at one point so standardized and ubiquitous that it was often overlooked, Murphy is bringing back the spark to tiramisu, and supporting a resurgence of respect for its subtlety. In that corner: Cannoli Just as tiramisu has a lovely translation, cannoli has one to rival it. The name of the crispy, sweet cream- or cheesefilled dessert simply means “tube of love.” While Ricotta is the most popular (and also the cheapest) filling, the pastry is up for delicious interpretation, so long as the love shines through. At Seattle’s Holy Cannoli, founder and owner Adrienne Bandlow takes a high-quality chef’s cream and cooks it down as though she were making Ricotta cheese, but without separating the curds from the whey. She then adds thickening agents. The result is a perfectly even-textured, hearty filling that is akin to pastry cream. Throughout her studies of cannoli, she’s come across a variety of filling preferences, from Ricotta to mashed cannellini beans with cocoa powder. Unlike Murphy, Bandlow didn’t grow up abroad. She did, however, grow up surrounded by Detroit’s large, vibrant, Italian-American community, watching her grandmother and aunt make pastas, soups, and desserts in her home kitchen and cultivating an innate love for Italian cuisine. When she was a teenager, her family moved to Seattle seeking better economic opportunities. Suddenly, Bandlow was dislodged from her familiar community, and she made herself at home by trying her hand in the kitchen. “Just like anyone who’s left their homeland and gone somewhere else, I had to figure out how to assimilate and still bring what I knew into my new life,” she says. “I couldn’t go to the deli down the street to get my favorite foods anymore, so I just started making them myself.” Without culinary training, Bandlow relied on calls to her grandmother for advice. She also trusted her own palate, which had developed from years of eating Italian classics.

The cannoli that would eventually change the course of her

career was, she admits, none too impressive. Bandlow’s boss at

a feminist nonprofit had mentioned off the cuff that she had

never been able to find a good cannoli in the Pacific Northwest.

To get some brownie points (“cannoli points,” as she calls it),

Bandlow rushed off to call her grandmother for a recipe and

some advice. Her first effort was fraught: the filling was thin

with chunks, and she remembers having to pack chocolate in

to keep it from seeping out of the sides of the shell.

Nonetheless, her boss was impressed, and Bandlow became

determined to perfect the dessert and share the little pastries

of love.

“After that first one—which was pretty embarrassing to

be honest—I just started making them for friends, and people

would get super jazzed about it,” she says. “Nobody knew

what they were, and they were stoked to discover an Italian

pastry that they’d never tasted.”

At the time, Bandlow was determined to go into the nonprofit

sector. But she began to realize that her pastries were

giving people more immediate, tangible joy than the complicated,

slow-moving legislation she had plans to tackle over the

course of her career. After fitting in as many entrepreneurship

classes as she could in a three-month window, Bandlow

opened Holy Cannoli in November 2011 to share the love.

Not all of Bandlow’s cannoli fit into the “subtle” category,

with full-flavored options like Limoncello and Salted Caramel

Pecan. Still, the original, Traditional cannoli with vanilla

cream and a hint of cinnamon and chocolate is and always

will be Bandlow’s favorite: a simple sweet that reminds her of her heritage.

VOCABULARY

- underrated - недооцененный

- subtleness - тонкость

- assimilate - усваивать

- fraught - чрезвычайный

- tangible - осязаемый

The Dark Night of the Soul

The famous proverb “It’s always darkest before the dawn,” emphasizes that in the darkest hour of the night–symbolical for situations when all hope feels lost–darkness has reached its peak, from which it constantly gets brighter until light starts to illuminate the world again. Just when you feel all hope is gone, things will get better when morning comes at last. What the proverb beautifully relates is that when you have reached your lowest ebb in a downward spiral of negativity, dawn arrives and brings light and hope to you.

The dark night of the soul is just what the proverb describes: an existential crisis that drags you to the ground. A situation so severe and evidently hopeless that it makes you question everything you ever thought to know. Not only that, but it also takes you all your interest in the joys this material world has to offer. Your senses are deprived—if not deadened—for a certain period of time.

But during this period of mental stillness and “self-inflicted” sensory deprivation you will come to a really important conclusion. You will realize what is really important to you in your life. A realization so profound and powerful that it will change the way you regard your situation for the rest of your life. You, for instance, began to realize that friendship and family were more important to me than anything else in the world. That sports cars were just a pile of nicely fashioned junk; likewise the technological tools were are playing around in this modern era. Just a scrapheap.

The dark night of the soul is the point where your life has reached a fork in the road with only two directions to choose from. Death or transformation.

And just as one has to go through a really tough period in life until things become better, an individual will experience their darkest hour of the soul, which will transform their life forever. In my opinion, it will change your life for the better in hindsight to wisdom, insight and a broader understanding of life in general. One only has to have the courage, so to speak, to see the windows that open when a door closes. Just as one can learn from failures there is a lot to gain from the dark night of the soul, even though it is a very rough and painful period of time that makes one feel like all hope is lost.

Everything happens for a reason.

Something good comes out of everything that happens.

Did you know that in the ancient mystery traditions, the would-be initiate had to symbolically experience his own death during the initiation ritual? The symbolic death experience was an allegory to the dark night of the soul. During the experience the initiate would be symbolically born again, after he had caught a glimpse behind the veil of the upper world (heaven). During “death” the initiate realizes and overcomes the downward spiral of their birth into ignorance and is enlightened with the powerful wisdom of the group. The symbolic dark night of the soul would lead the initiate to metaphorically rise from the dead, proving the maturity to be instructed in the secrets of the mystery school.

And this is exactly what happens during the dark night of the soul, even though in a somewhat tougher and more painful manner. And a part of you dies during this experience.

The Dark Night of the Soul

But all hope is not lost, far from it! In fact, a far more powerful and wiser individual arises out of such a situation. And instead of waiting for dawn to illuminate the world again this person will become the beacon of light that shines through the pitch-black night, sharing hope and courage for those that are around.

In a sense, the dark night of the soul is necessary for an individual’s growth and development. It is the integral part of a life’s journey that turns everything upside down and leaves only the things behind that are important for the voyager and their progress. Without such an experience there would be no room for growth. There is no progress without struggle, as they say. Life would be a stagnating experience without the slightest chance for development. What would seem like a perfect world would sooner or later turn into a hellish nightmare from which one desperately would try to wake up.

If you are experiencing your personal dark night of the soul at this moment in time, it is important that you do not give up! Don’t allow it to consume your hope for a better future. Don’t let it take all your courage. Try to stay as calm as possible and see how things unfold. Most likely you will experience the gradual dismantling of your personality. The three primordial questions about existence might arise, maybe for the first time in your life. “Who am I? Where did I come from? And where am I going?” If you have the courage to pursue these questions you will find the right answers that will provide you a new hope.

Whatever is happening to you at this moment will pass eventually, making room for something new and positive. Remind yourself that something good evolves out of everything bad that happens to you. With this kind of powerful mindset nothing will be able to stand in your way. Have the courage to seek for the new opportunities that will arise as you are experiencing your darkest hour.

In more technical terms, the dark night of the soul is the process that quietens the mind and brings the soul to a peaceful serenity during which a transformation can take place. And one day you will look back at what you’ve gone through, how it affected you and how it profoundly changed your whole life and you will notice that it is you who has become a beacon of light, lightening the dark for others during their personal crisis. Then you know it was worth it.

VOCABULARY

- ebb - отлив

- deadend - тупик

- pile - куча

- veil - вуаль

- enlightened - просвещенный

- beacon of light - путевая звезда

- evolve -

The art of listening

Listeners are the unsung heroes and heroines of classical music. Composers have their reverent biographers, their biopics and statues in the public square; performers have ecstatic fans, the limos and the recordings contracts. But who cares about the poor old listener, the third member of the ‘Holy Trinity’ of music, as Benjamin Britten described him or her? It’s not as if listeners don’t earn their keep. Listening is a strenuous business. Witness this report of four ardent listeners to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony at the Queen’s Hall, sometime before the First World War: ‘Here Beethoven started decorating his tune [the first variation of the theme], so she [Helen] heard him through once more, and then she smiled at her cousin Frieda. But Frieda, listening to Classical Music, could not respond. Herr Liesecke, too, looked as if wild horses could not make him inattentive; there were lines across his forehead, his lips were parted, his pince-nez at right angles to his nose, and he laid a thick, white hand on either knee. And next to her was Aunt Juley, so British, and wanting to tap.’

Admittedly, that scene from EM Forster’s Howard’s End is only fiction. But it contains a truth. Listening to classical music isn’t just humming along to the tunes; it’s an attempt to divine a vision vouchsafed to the composer, conveyed in patterns of notes to the listener in ways that aren’t obvious. The vision is sometimes hidden, and can be revealed only by attentive listening and patient study. It’s hard to believe listeners were always so strenuously high-minded, and in recent decades there’s been a concerted effort to find out what really goes on in people’s hearts and minds (and their bodies too) when they listen. Philosophers, psychologists, sociologists and cultural historians have all found this subject fascinating. As, of course, have musicologists.

This interest in how people actually listen to classical music (and other sorts of music) is a recent phenomenon. Well into the 20th century, discussion about listening was prescriptive, not descriptive – there was a right way to listen and a right way to respond, and woe betide anyone who got it wrong. In 1897, Henry Krehbiel published his How to Listen to Music, a weighty tome full of fingerwagging advice. There’s a section on ‘Blunders by Tennyson, Lamb, Coleridge, Mrs Harriet [Beecher Stowe]’, a ‘warning against pedants and rhapsodists’ and this stern reminder in the contents page: ‘Taste and judgement not a birthright – the necessity of antecedent study’.

It’s a wonder anyone dared to go to a concert in the late 19th century. This attitude lingered well into the 20th century, though the writers’ tone was more friendly. Aaron Copland’s What to Listen for in Music and Antony Hopkins’s Talking about Music still assume that listening is a skill, and that without it we miss much that music has to offer. This determination to prescribe the right way to listen to music was so ingrained that writers yielded to it, even when they thought they were being descriptive. In his 1941 essay On Popular Music, that severe philosopher Theodor Adorno takes a big stick to pop songs for being so perfectly formulaic. He says this enforces a trivial sort of listening, in contrast to classical music where the details and the whole form are dynamically interrelated. ‘The scheme (of a pop song) emphasises the most primitive harmonic facts no matter what has harmonically intervened,’ he says primly. ‘Complications have no consequences.’ This means that details matter more than the whole and, consequently, ‘the listener becomes prone to evince stronger reactions to the part than to the whole.’

And where’s his evidence for that assertion? There isn’t any – Adorno is setting up a principle, and assuming the facts will obediently follow. That high-handed attitude to reality won’t do any more. Today’s scholars have come round to thinking that a certain humility is in order. Looking into how people actually listen, rather than telling them how they ought to listen, is the order of the day.

To do that requires facts whi ch by their nature are elusive, as listening has become an increasingly private affair. Some researchers focus on the present, doing patient field-work in the places people actually use music: work places, living rooms, at the gym. Some focus on the past, patiently sifting the evidence for clues as to how (or even whether) they listened to music.

For researchers interested in how we listen now, no sort of music is too humdrum, and no music too ephemeral. They are interested in the way music weaves itself into our everyday lives. One fascinating journal article I came across is entitled ‘Personal collections as material assemblages: A comparison of wardrobes and music collections’. In this world-view, there are no hierarchies. The experience of half-listening to a Bon Jovi album while doing the ironing is just as revealing of the warp and woof of human feelings as a Beethoven quartet listened to in rapt silence at Wigmore Hall.

Turning to the other sort of research – the sort that examines modes of listening in cultures distant from ours – is if anything even more subversive of received ideas about ‘proper’ ways of listening. If by ‘distant’ we mean non-Western cultures, then we may find that the listening experience is not just elusive but non-existent. In many cultures everyone participates, either by playing, dancing or joining in the ritual which the music articulates. There are no listeners as such.

Even within the field of ‘classical music,’ the presence of rapt, attentive listeners is not a given. If anything it’s the exception, a late flower of an art music culture which could only blossom in the special climate of the Romantic era. Before that, music wasn’t thought of as the vehicle for a special kind of intimate, private experience. Its role was social, and if people listened, it was so they could display their knowledge and engage in disputes about the quality of this or that singer or player. A writer on medieval poetsingers named Raimon Vidal declared that ‘one of the most worthy things in the world is to praise what is to be praised and to condemn what is to be condemned’.

Another way of showing skill and expertise was to join in, and the criteria for making a good showing weren’t necessarily musical. The 16th-century Chronicle of Castile suggests that sophisticated art songs, of the kind we would enjoy for their musical value, had a lowly status as background to carousing, whereas popular songs, of the kind we would find monotonous, took centre-stage. Everyone joined in, as the simple repeating structure created a framework for guests to outdo each other in improvised verbal dexterity.

Another way of showing skill and expertise was to join in, and the criteria for making a good showing weren’t necessarily musical. The 16th-century Chronicle of Castile suggests that sophisticated art songs, of the kind we would enjoy for their musical value, had a lowly status as background to carousing, whereas popular songs, of the kind we would find monotonous, took centre-stage. Everyone joined in, as the simple repeating structure created a framework for guests to outdo each other in improvised verbal dexterity.

Jump forward to the early-18th century, and we find that listening to music too attentively was actually thought to be vulgar. ‘There is nothing so damnable as listening to a work like a street merchant or a provincial just off the boat,’ says a character in La Morlière’s novel of 1744, Angola. Forty years later, the writer Fanny Burney describes a concert ‘to which no one of the party but herself had any desire to listen, no sort of attention was paid; the ladies entertaining themselves as if no orchestra was in the room, and the gentlemen, with an equal disregard to it, struggling for a place by the fire, about which they continued hovering till the music was over.’

But a change was in the air. The cult of sensibility which arose later in the century favoured indefinable emotions, the sort that couldn’t be pinned down to a definite image or narrative. Instrumental music was tailor-made to satisfy this new appetite, and now came into its own. A genuine culture of listening came into being, which in turn prompted a respect for the integrity of musical works. Previously these had been chopped into separate movements or mixed and matched into medleys or pasticcios. To clap between movements of a pasticcio was acceptable; to clap between movements of a Beethoven symphony began to seem wrong.

The new cult of reverent silence was exemplified by John Ella’s Musical Union, a concert-giving subscription society founded in London in 1845 whose motto was ‘the greatest homage to music is to listen in silence’. In his Cyclopaedic Survey of Chamber Music, WW Cobbett recalled that ‘it was a sight for the gods when Ella rose from his gilded seat, held aloft his large, capable hands, clapped them, and called for SILENCE in a stentorian voice. After this, no lord or lady present, however distinguished, dared to interrupt the music by fashionable or any other kind of chatter.’ It wasn’t long before the new fashion for silence became a norm to be sternly enforced. ‘It is exceedingly vulgar to annoy your neighbors by beating time, humming the tunes, or making. unseemly and ridiculous gestures of admiration,’ said George Watson’s Etiquette for All in 1861. Which is more or less where we’re at today – except that once again, change is in the air. There’s a sense that concert behavior has become too formal, and that classical music can only win new audiences by relaxing the rules. But in any case, how true is the ideology of ‘pure music’ to the way we actually attend to music? Don’t we all have mixed motives when going to a concert, which is as much to do with meeting like-minded people as it is to listening to masterworks? To say that isn’t to denigrate music itself. It simply acknowledges that the role of music in our lives is complex, and as varied as human life itself.

VOCABULARY

- limos - лимузины

- inattentive - невнимателен

- vouchsaf - сподобиться

- linger - задерживаться

- consequence - следствие

- elusive - неуловим

- humdrum - буднично

- hierachies - иерархии

- arose - возникать

- pasticcios - смесь

Preventing burnout

If constant stress has you feeling disillusioned, helpless, and completely worn out, you may be suffering from burnout. When you’re burned out, problems seem insurmountable, everything looks bleak, and it’s difficult to muster up the energy to care—let alone do something about your situation.

The unhappiness and detachment that burnout causes can threaten your job, your relationships, and your health. But burnout can be healed. You can regain your balance by reassessing priorities, making time for yourself, and seeking support.

What is burnout?

You may be on the road to burnout if:

- Every day is a bad day.

- Caring about your work or home life seems like a total waste of energy.

- You’re exhausted all the time.

- The majority of your day is spent on tasks you find either mind-numbingly dull or overwhelming.

- You feel like nothing you do makes a difference or is appreciated.

- Recognize – Watch for the warning signs of burnout

- Reverse – Undo the damage by managing stress and seeking support

- Resilience – Build your resilience to stress by taking care of your physical and emotional health

| Stress vs. Burnout | |

Stress | Burnout |

Characterized by overengagement | Characterized by disengagement |

Emotions are overreactive | Emotions are blunted |

Produces urgency and hyperactivity | Produces helplessness and hopelessness |

Loss of energy | Loss of motivation, ideals, and hope |

Leads to anxiety disorders | Leads to detachment and depression |

Primary damage is physical | Primary damage is emotional |

May kill you prematurely | May make life seem not worth living |

Source: Stress and Burnout in Ministry | |

Work-related causes of burnout

- Feeling like you have little or no control over your work

- Lack of recognition or rewards for good work

- Unclear or overly demanding job expectations

- Doing work that’s monotonous or unchallenging

- Working in a chaotic or high-pressure environment

- Working too much, without enough time for relaxing and socializing

- Being expected to be too many things to too many people

- Taking on too many responsibilities, without enough help from others

- Not getting enough sleep

- Lack of close, supportive relationships

- Perfectionistic tendencies; nothing is ever good enough

- Pessimistic view of yourself and the world

- The need to be in control; reluctance to delegate to others

- High-achieving, Type A personality

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Start the day with a relaxing ritual. Rather than jumping out of bed as soon as you wake up, spend at least fifteen minutes meditating, writing in your journal, doing gentle stretches, or reading something that inspires you.

- Adopt healthy eating, exercising, and sleeping habits. When you eat right, engage in regular physical activity, and get plenty of rest, you have the energy and resilience to deal with life’s hassles and demands.

- Set boundaries. Don’t overextend yourself. Learn how to say “no” to requests on your time. If you find this difficult, remind yourself that saying “no” allows you to say “yes” to the things that you truly want to do.

- Take a daily break from technology. Set a time each day when you completely disconnect. Put away your laptop, turn off your phone, and stop checking email.

- Nourish your creative side. Creativity is a powerful antidote to burnout. Try something new, start a fun project, or resume a favorite hobby. Choose activities that have nothing to do with work.

- Learn how to manage stress. When you’re on the road to burnout, you may feel helpless. But you have a lot more control over stress than you may think.

Sometimes it’s too late to prevent burnout—you’re already past the breaking point. If that’s the case, it’s important to take your burnout very seriously. Trying to push through the exhaustion and continue as you have been will only cause further emotional and physical damage.

While the tips for preventing burnout are still helpful at this stage, recovery requires additional steps.

Burnout recovery strategy #1: Slow down

When you’ve reached the end stage of burnout, adjusting your attitude or looking after your health isn’t going to solve the problem. You need to force yourself to slow down or take a break. Cut back whatever commitments and activities you can. Give yourself time to rest, reflect, and heal.

Burnout recovery strategy #2: Get support

When you’re burned out, the natural tendency is to protect what little energy you have left by isolating yourself. But your friends and family are more important than ever during difficult times. Turn to your loved ones for support. Simply sharing your feelings with another person can relieve some of the stress. The other person doesn’t have to ret to “fix” your problems; he or she just has to be a good listener. Opening up won’t make you a burden to others. In fact, most friends will be flattered that you trust them enough to confide in them, and it will only strengthen your friendship.

Burnout recovery strategy #3: Reevaluate your goals and priorities

Burnout is an undeniable sign that something important in your life is not working. Take time to think about your hopes, goals, and dreams. Are you neglecting something that is truly important to you? Burnout can be an opportunity to rediscover what really makes you happy and to change course accordingly.

VOCABULARY

- worn out - изношенный

- insurmountable - непреодолимый

- muster up - собирать

- reassessing - переоценивать

- overwhelmed - перегружен

- high-pressure - высокое давление

- reluctance - нежелание

- accomplishment - достижение

- withdrawing - снятие

- boundaries - границы

The American Dream

“My mother believed you could be anything you wanted to in America. You could open a restaurant. You could work for the government and get good retirement. You could buy a house with almost no money down. You could become rich. You could instantly become famous.”

Thus begins “Two Kinds,” a short story by the acclaimed Chinese-American author Amy Tan. Telling the tale of two cultures, the story tells of Jing Mei, a young American girl whose mother, having lost everything in China, wants to realize her own dreams through her daughter, whom she hopes will become a child prodigy. While this story of parent-child conflict is universal, the mother's unfailing belief in her daughter's destiny is distinctly American. Pervasive throughout our entire culture, the idea of the American Dream can be seen in the songs of such musicians as Elvis and Bruce Springsteen, the literary works of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Tennessee Williams, and many of our Hollywood movies. Sometimes it is endorsed as something positive and worth striving for; at other times it is harshly criticized. Members of marginalized or minority groups in the US, such as African-American folk singer Tracy Chapman and Latino writer Junot Diaz, seek to show how it is not. But, no matter how people choose to view it, what exactly is this dream that looms so large in American consciousness?

The basic idea that most people have of the American Dream is the one which Tan expresses at the beginning of her story. It is the idea that a person can go from rags to riches, beginning with nothing and ending up with a big house, a stylish car, and enough wealth to ensure an even better future for one's children. However, the dream is actually more complex than this. In Arthur Miller's play Death of a Salesman, which is one of the most famous literary explorations of the American Dream, we meet Willy Loman, an aging salesman who has fallen into a depression and ultimately commits suicide due to his conflicts with his family members as well as his own feelings of inadequacy. He is a man who has sought the American Dream and failed to achieve it. However, while Willy is indeed preoccupied over financial matters (his family is in deep debt), we soon realize that money is not what he yearns for. We learn that as a young man he chose to become a salesman not for material gain, but for recognition and affection. He recalls seeing an old salesman who was loved by all his clients and, after his death, was honored with a splendid funeral attended by hundreds of salesmen and buyers. For Willy Loman the American Dream consists not in wealth or even fame, but in honor, respect and love. Instead, he ends up with only failure and pity from the tiny smattering of people who attend his meager funeral. However, while Arthur Miller criticizes the American Dream by revealing the havoc it wreaks on a man and his family, he also expresses some admiration for it and suggests that there is a degree of nobility in the way Willy has lived and died. “A salesman has got to dream,” says Willy's neighbor Charley at the funeral. “It comes with the territory.”

In order to better understand the origins of this dream and its role in our history, we need only look at on object we use everyday: our money. Examining the US dollar bill, we see three mottos written on the seal. One of these is “E pluribus unum,” which means “Out of many, one.” This is the classic idea of democracy handed down to us from ancient Greece, the idea of uniting a diversity of people into the single entity of a nation. This idea is common to all democratic nations and is not unique to the United States. However, the next motto, “Novus Ordo Seclorum” (“A new order of the ages”) brings us closer to the idea of the American Dream. The United States was founded not merely because of colonists' disputes with Britain over taxes, but on ideas of justice and liberty. In declaring independence from Britain and later drafting the world's first written constitution, the founding fathers were essentially creating a new nation from scratch, a new order. This required a great deal of optimism, imagination, determination, and indeed a great deal of dreaming. However, it is the last motto - “Annuit Coeptis”- that most clearly reveals the American Dream at its essence. Translated into English, it means, “He has favored our endeavors,” and this “He” is implied to mean God. Needless to say, this motto is perplexing and indeed more than a little disturbing, for it implies that there is something exceptional about the United States, that our actions have some sort of divine sanction. However, looking at our country's history of expansion from coast to coast and intervention in world affairs, we definitely see that this is the exact attitude behind many of our actions and decisions. And while the US is by no means the only nation in the history of the world to have held this belief, it has perhaps taken it to heart more than most others.

Far from being a simple desire for riches or advancement, the American Dream is a complex phenomenon that has produced many reactions and counter-reactions in people. In the last century it led some people to support and give their lives in a very controversial war—the Vietnam War—and inspired others to march in protest of that same war. It has led some to ignore questions of ethics in their pursuit of wealth and fame, while it has led others to devote their lives to the task of making a difference in their country and the world. It is the dream of Jay Gatsby in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel and also the dream of Martin Luther King. It may be interpreted in hundreds of ways, criticized, rejected or pursued. But, no one can question that it is an integral part of our culture's foundation and invariably is here to stay.

VOCABULARY

- ensure - обеспечивать

- havoc - опустошение

- implie - предполагать

- justice - справедливость

- loom - мираж; маячить

- marginalized - не придавать особого значения

- minority - меньшинство

- motto - девиз

- yarn - тосковать

The Choice

Say what you will about 2004’s The Notebook, but Nick Cassavettes’ particular spin on the Nicholas Sparks formula had a few things going for it: a pair of real movie stars in Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams, a period setting that couched their old-fashioned star-crossed lover routine in some interesting production design, and an ending that owned up to the soap opera pathos it was all leading up to. The same cannot be said for the remainder of the Sparks Cinematic Universe, of which The Choice is but the latest installment in this series of feel-good whitebread bodice-rippers.

Set in some kind of Levi’s ad version of North Carolina, The Choice follows rakish good ol’ boy Travis Shaw (Ben Walker), the kind of proud child of the South who spends his time gallivanting around with whatever filly might pop his way, healing puppies with his veterinarian dad (Tom Wilkinson, doing his best) and wearing aviator sunglasses with his equally-chiseled friends. This all changes when bookish Gabby (Teresa Palmer) moves into the house next door with her glasses and frumpy sweatsuits, all set to marry sentient block of wood Tom Welling. If you’ve seen the trailer, or have two brain cells to rub together, you can see where this is going.

For what it’s worth, the movie takes its title to heart: after all, we get not one, but two monologues in voiceover from Walker in which he essentially describes the nature of narrative conflict. “Y’see, in your life there are choices, y’hear? And one choice will lead y’all down one road, and t’other will lead y’all down a different one. Tarnation, decisions are tough!” The film wants you to believe the titular ‘Choice’ is one of many things. First, it’s the decision whether or not to fall in love with each other, then it’s whether or not to tell Gabby’s boyfriend, then it’s whether to unplug Gabby from life support months after she goes into a coma after a car accident (filmed with the same bloodlessness as everything else).

For all the movie’s blathering about making tough choices and learning to move forward with the consequences, the characters never really have to commit to any hard decisions. The surrounding characters will just tell them what to do, the most complicated stuff will happen off screen, or – most infuriatingly – everything will just work out in the end. Even when women repeatedly and passionately refuse a marriage proposal, for instance, their parents are there to cheekily tell her that the stranger in front of them is The One because you blushed at them. Throw in your garden-variety nods to a higher power, and you’ve got all the makings for a vapid romantic drama that’ll leave your grandma in tears.

For a film that hinges so much on the chemistry and charm of its two leads, it’s tough to recommend The Choice on even those grounds. Walker brings a laconic, Nathan Fillion-esque charm to Travis, though it’s a shame he has to waste it on this material. Palmer, however, is saddled with the even harder job of making such an abrasive, hypocritical and indecisive character as Gabby relatable and likable. Suffice to say, neither lead comes out looking good – unless you count the model-worthy bodies they had to get for this film. I’ll say this: there are six reasons to see The Choice, and they’re all studded along Ben Walker’s stomach.

Despite even these modest plaudits, there’s nothing challenging, surprising or enthralling in any of the 110 minutes of The Choice. Like the rest of Sparks’ oeuvre, The Choice offers anemic, uncomplicated drama for particularly undiscerning audiences looking for someone to tell them that love and relationships aren’t as hard as they are in real life. Just spend the movie gawking at the cute dogs that bring Walker and Palmer together, and you might stand a chance of getting through The Choice’s nearly two-hour runtime.

VOCABULARY

- equally-chiseled - одинаково точеные

- hinges - петли

- infuriatingly - невыносимо

- nod - кивать

- oeuvre - творчество

- sentient - чувствующий, ощущающий, мыслящий

- y’all - You and all

A brief history of young adult literature

Back in 1998, just as Harry, Bella and Katniss were on the verge of owning the front shelves of bookstores everywhere, the Young Adult Library Services Association launched Teen Read Week in an effort to mold adolescent bookworms.

With young adult literature regularly burning up the bestseller lists, it's clear many young adults don't need an excuse to seek out the written word: Sixteen- to 29-year-olds are the largest group checking out books from their local libraries, according to a Pew survey.

Wizards, vampires and dystopian future worlds didn't always dominate the genre, which hit its last peak of popularity in the 1970s with the success of controversial novels by the likes of Judy Blume. In the years between, young adult has managed to capture the singular passions of the teen audience over a spectrum of subgenres.

Now, as the book industry enjoys a second "golden age of young adult fiction," according to expert Michael Cart, it bears asking why young adult fiction has become so successful. The proof just may be in the timeline.

The very beginning

The roots of young adult go back to when "teenagers" were given their own distinction as a social demographic: World War II. "Seventeenth Summer," released by Maureen Daly in 1942, is considered to be the first book written and published explicitly for teenagers, according to Cart, an author and the former president of the Young Adult Library Services Association. It was a novel largely for girls about first love. In its footsteps followed other romances, ands sport novels for boys.

The term "young adult" was coined by the Young Adult Library Services Association during the 1960s to represent the 12-18 age range. Novels of the time, like S. E. Hinton's "The Outsiders," offered a mature contemporary realism directed at adolescents. The focus on culture and serious themes in young adult paved the way for authors to write with more candor about teen issues in the 1970s, Cart said.

The first golden age is associated with the authors who the parents of today's teens recognize: Judy Blume, Lois Duncan and Robert Cormier. The young adult books of the 1970s remain true time capsules of the high school experience and the drama of being misunderstood. Books like Cormier's "The Chocolate War" brought a literary sense to books targeted at teens.

But once these books devolved into "single-problem novels" -- divorce, drug abuse -- teens grew tired of the formulaic stories. The 1980s welcomed in more genre fiction, like horror from Christopher Pike and the beginning of R.L. Stine's "Fear Street" series, and adolescent high drama a la "Sweet Valley High," while the '90s were an eclipse for young adult. With fewer teenagers around to soak up young adult lit due to low birth rates in the mid-1970s, books for tweens and middle-schoolers bloomed. But a baby boom in 1992 resulted in a renaissance among teen readers and the second golden age beginning in 2000, Cart said.

The most challenged books

The most challenged books

"When I was a teen in the '90s, there were probably three shelves of teen books I wanted to read," said Shannon Peterson, former president of the Young Adult Library Services Association. "Now, I feel like it's evolved from three shelves to whole hallways of books."

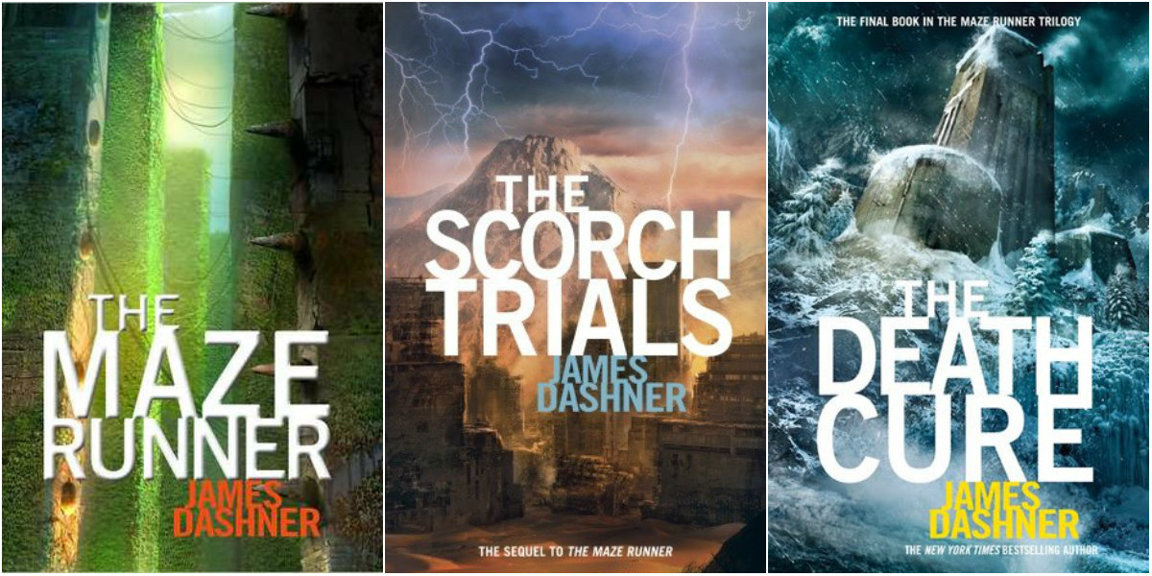

The book world began marketing directly to teens for the first time at the turn of the millennium. Expansive young adult sections appeared in bookstores, targeting and welcoming teens to discover their very own genre. J.K. Rowling's well-timed "Harry Potter" series exploded the category and inspired a whole generation of fantasy series novelists, Cart said. The shift led to success for Stephenie Meyer's "Twilight" vampire saga and Suzanne Collins' futuristic "The Hunger Games."

But why did paranormal and dystopian tales connect so well with teens?

"Just like adolescence is between childhood and adulthood, paranormal, or other, is between human and supernatural," said Jennifer Lynn Barnes, a young adult author, Ph.D. and cognitive science scholar. "Teens are caught between two worlds, childhood and adulthood, and in YA, they can navigate those two worlds and sometimes dualities of other worlds."

Now, reveling in the continued success of fantasy subgenres and series, young adult fiction is enjoying a sustained boom rather than an afterglow.

Young adult books that changed our lives

Nostalgic hallmarks

"It's not surprising that YA is always dealing with transformation, whether it be realistic or supernatural," author and publisher Lizzie Skurnick said. "It's the only genre that can always be both. It shows teen life in full chaos. And that means constant change."

Skurnick is also devoted to reissuing classic young adult novels, from the 1930s to the 1980s.While young adult spans and mashes up multiple genres, it connects readers to transformation stories best through emotion.

When David Levithan was helping develop Scholastic's teen imprint, PUSH, in the late '90s, he and his team spoke directly with teens over the course of four years to discover what they wanted in their literature. PUSH launched a line of novels by debut authors with authentic voices in 2001.

"Teens wanted things that were real, that they connected with," Levithan said. "It doesn't have to reflect reality directly. They love 'The Hunger Games' not because it's real in that it happens, but the emotions there are real, and it's very relatable."

Young adult novelists don't shy away from tackling the deepest and darkest issues that teens face, from identity struggles and sexual abuse to drug/alcohol use and suicide. Authors like John Green write about the best and worst of adolescence fearlessly and honestly, building a trust within readers, Peterson said.

Author Meg Cabot tried to find books she could relate to as a teen, but the "single-problem" novels that resulted in girls dying for their choices frustrated her. She wanted to read the "science fiction novels about girls spying on other planets."

Now Cabot has written more than 45 young adult books. "The whole reason you're reading is because you want some hope that you're going to get through whatever you're going through. I know how hard it was as a teenager, and I understood how it felt to be an outsider. I want to be able to offer people hope."

Meg Cabot's teen escapism and empowered heriones

Turning the page

Because young adult fiction is always changing, anything goes, said Elissa Petruzzi, Web and young adult section editor for Book Club Magazine. From sci-fi/fantasy, paranormal and dystopian to classic romance, mystery and contemporary favorites, writers can explore any subject, and readers are eager for new worlds.

Contemporary standalones, or non-serial books, have returned to the forefront as a lighter response to dark paranormal and dystopian series, Barnes said.

A real opportunity for growth lies in diversity, Peterson said, although young adult already surpasses children's fiction in that aspect. Cart is pleased to see more gay, lesbian and transgender characters in young adult books but admits that there is a multicultural hole, especially for Hispanic teens.

Cabot strives to amp up the empowerment angle for girls. As a teen, she always looked for role model heroines, so all of her female characters "kick ass."

The genre is also just as open to male readers as it is to females, said Erin Setelius, a writer for theYA Book Addicts blog. "Boys and girls can fall in love with the same books."

Because filling gaps is an area where young adult succeeds, the "new adult" genre has emerged over the past few years (beginning with St. Martin's Press coining the phrase in 2009), featuring characters in their late teens and early 20s going through the college experience and a second adolescence. Only time will tell whether it's a trend or a budding genre, Petruzzi said.

Young adult lit has become popular with readers of all ages and has even allowed parents to see what their teens care about through what they're reading, Skurnick said. After all, 55% of young adult books purchased in 2012 were bought by adults between 18 and 44 years old, according toBowker Market Research.

"I don't think people are reading it just to relive their teen moments," Peterson said. "It's so interesting to see what happens when there is all of that living, emotion and the heaviness of all that emotion, without the experience. It's such a terrible and beautiful thing to witness."

VOCABULARY

- adolescene - подростковый возраст, юность

- Cart - тележка

- candor - откровенность

- contemporary - современный

- controversical - спорный

- distinction - различие

- excuse - оправдание

- mature - зрелый, созревать

- seek - искать, стремиться

- soak up - впитывать

The UK in Space

With Major Tim Peake due in December 2015 to become the first British astronaut funded by government.

In fact, the United Kingdom was the third country in the world to operate a satellite - with the launch of Ariel-1 in 1962.

The US were keen to work with their allies to launch experiments on their satellites, and Ariel-1 was the first such collaboration. Nasa would provide the rocket and build the satellite, and the experiments on board were developed by the Science Research Council, the UK's agency charged at the time with responsibility for space research. In all, six scientific instruments were supplied by the UK for the satellite, designed to investigate the relationship between the ionosphere, cosmic and solar rays.

The launch from Cape Canaveral on 26 April 1962 of Ariel-1 was actually one of great relief for Nasa, after some earlier rocket disasters, and its successful deployment in orbit made the United Kingdom the third country to operate a satellite. Ariel-1 operated perfectly apart from the failure at launch of one of the solar experiments. Perfectly, this is, until the 9 July, when as Ariel-1 was passing over New Zealand, the US Air Force detonated a high altitude nuclear test on the other side of the world. The result was the creation of a new radiation belt around the Earth, and this eventually affected one-third of all satellites in low earth orbit, including Ariel-1.

For a while, not even Nasa knew about the test, but later it became clear what had happened, and that it had badly affected Ariel-1's ability to generate its own electrical power from the solar generators. Ironically, thanks to Ariel-1's on-board electron detectors, the satellite was one of four which provided invaluable data about the detonation, showing the high energy electrons from the bomb appeared at high latitudes very shortly after the explosion. Unfortunately, Ariel-1 didn't last too long after the detonation, and eventually decayed from orbit in 1976.

VOCABULARY

- allies - союзники

- altitude - высота

- belt - ремень

- charged - заряженный

- Council - Совет

- decayed - гнилой

- funded - создание финансового резерва

- invaluable - бесценный

- keen to - стремиться

- latitudes - широты

- nuclear - ядерный

- operate - работать, управлять, действовать

The most challenged books

The most challenged books